OPINION

Sustainable Path to Prosperity

The most immediate consequence of a state-mandated CSR framework is a boost to

public-private partnerships. However, for the sake of reaching a proficient partnership,

phase two shall enact necessary controls. I would like to see regional governments sitting

at the table with major corporations assigning areas of investment and intervention.

By Ilaria Gualtieri

I would like to start this article by making a heartfelt confession. As you may well know by now, I am a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and sustainability freak. However, you may not be aware that I am deeply in love with India, its profound culture, history, natural richness, its fascinating diversity, so much that I have recently started learning Hindi.

I particularly value this month’s topic since I follow with great interest the developments that contribute to a prototypical change to one of the world’s largest and most promising nations. prime minister Narendra Modi’s address at United Nations Sustainable Development Summit in 2015 summarises much of the country’ spirit: “We are committed to a sustainable path to prosperity. It comes from the natural instinct of our tradition and culture. But it is also rooted firmly in our commitment to the future. We represent a culture that calls our planet Mother Earth.”

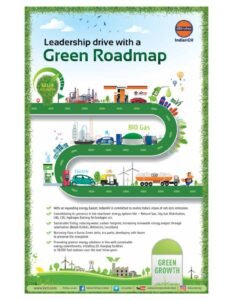

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) set by India along with the leadership undertaken within the Paris Agreement demonstrate an ambitious and purposeful plan: renewable energy, afforestation, transport, health, public service reforms, human rights, empowerment of women, Blue Revolution, waste management and smart cities. Above all, I appreciate that the country sustainable path to prosperity is not acquiescent to a western-style development model which proved inherently unsustainable. India has incorporated a forward looking, lesson-learned- based approach that could potentially transform not only the vast country, but also potentially influence the development of a continent and the rest of the world. Within the CSR panorama, the 2013 Ministry of Corporate Affairs’ Companies Act is an interesting precedent.

Its greatest outcome is the establishment of a state-mandated CSR system. The innovative element is that the state did so not only in terms of requiring a financial commitment, but asking companies to drastically change the way they do business by integrating a range of CSR principles and ― mostly ― management practices. The act mandates companies to set a CSR vision, policies, a project execution plan, especially, a road map for achieving long-term goals, requiring the creation of a dedicated team and frameworks, while disclosing information on company’s website. The Indian Government has been accused of setting technocratic sustainability. To begin with, I personally disagree that this is about sustainability. The principles are more about CSR, or the set up of a management system to include responsibilities beyond regulation and ethics. Sustainability includes and mostly details the same set of principles, however, looking at the future armed with a set of KPI’s and measurable steps.

The nine CSR principles do not elucidate how sustainability is mapped; they do not establish measurable targets for the corporate sector to help furthering the state’s agenda. Yet, India had to start somewhere. Sincerely speaking, we cannot wait for corporations to decide when it is the right time, we cannot just endorse the western voluntariness principle according to which corporations shall grow and thrive by first doing bad and then start cleaning up. State’s carrot and sticks intervention to promote responsible practices is not new. If it wasn’t for regulations, European Union would not have achieved certain remarkable results in terms of reporting and environmental performance. The other side of the coin, however, is that CSR is not a franchise, it cannot be imposed: it shall mature within a receptive environment where the need to put in place certain practices has naturally evolved. Nevertheless, research shows that sustainability or CSR reporting is often the first action implemented upon kicking off a real integration process.

Modern India clearly sees the economic sector as a partner. Thus it not only wants, but requires a change. A drastic CSR-economic revolution finds in regulation the best way to ensure the message is received. The government needs allies to achieve its ambitious goals, the private sector is now bond to substantiate a social responsibility often blathered but seldom demonstrated. There is no right or wrong in developing such an immense task. There are a plenty of frameworks and national CSR indexed around the world, it is all about choosing the right fit to the current needs. So, this is a bold state-led public-private partnership educational attempt. It all depends on its implementation.

A mandated transparency and accountability framework poses the likely risk that companies rush their commitment to comply, creating a superficial strategy as a tick-box exercise. The act in fact mandates companies to create and disclose a CSR vision, mission and overall philosophy (98 per cent top 100 listed companies complied, 90 per cent provided details), create a CSR committee (64 per cent exceeded the target, 55 per cent include women, 82 per cent have two or more members), expound how the 2 per cent of average net profit has been spent in reference to the policy disclosed.

The top 100 companies delivered very well on the strategy and committee creation. However, only 57 per cent presented policy links on their website while just 46 per cent published a detailed road map. Setting a CSR strategy is not an overnight exercise. It requires awareness, maturity and the inclusion within corporate decisionmaking of societal and environmental concerns, a deep comprehension and prioritisation of stakeholders, awareness of market- and work-place best practices, and especially appropriate governance and processes. Overall, the positivity stands into forcing a “CSR mindset” into companies. The first three to five years will be learning ground; real framework and road maps shall naturally come after this period. The data on the companies’ ability to explicate the CSR spend contribution to the overall plan further confirms the muddle: 42 per cent failed disclosure, 21 per cent did not refer to policy; moreover, only 40 per cent provided details on focus areas and 25 per cent on the stakeholders’ impact.

This further demonstrates an early stage of CSR integration, revealing the lack of a fundamental element within corporate sustainability: the materiality principle. Materiality is defined by GRI as the ability of a report or strategy to reflect the organization’s significant socio-environmental impact. It is an evolving process made of identification, prioritization, assessment and review. This principle asks companies to assess, comprehend, evaluate and include in their decision-making a wide set of responsibilities — governance, society and environment. Companies require time to gauge the situation, pinpoint their strengths, build and test internal processes, and identify partners and focus areas where they can provide the best results to both the society and the company itself. Among the positive notes is the increased average spend, involving 70 per cent companies, with 18 per cent committed to carry on the spend this year.

Similarly, the major areas of intervention reflect some of the state’s priorities: health, education, environment and rural development, with philanthropy relegated at 3 per cent. Above all, I appreciate that the country sustainable path to prosperity is not acquiescent to a western-style development model which proved inherently unsustainable. India has incorporated a forward looking, lessonlearned- based approach that could potentially transform not only the vast country, but also potentially influence the development of a continent and the rest of the world. Within the CSR panorama, the 2013 Ministry of Corporate Affairs’ Companies Act is an interesting precedent. Its greatest outcome is the establishment of a state-mandated CSR system.

The innovative element is that the state did so not only in terms of requiring a financial commitment, but asking companies to drastically change the way they do business by integrating a range of CSR principles and ― mostly ― management practices. The act mandates companies to set a CSR vision, policies, a project execution plan, especially, a road map for achieving long-term goals, requiring the creation of a dedicated team and frameworks, while disclosing information on company’s website. The Indian Government has been accused of setting technocratic sustainability.

To begin with, I personally disagree that this is about sustainability. The principles are more about CSR, or the set up of a management system to include responsibilities beyond regulation and ethics. Sustainability includes and mostly details the same set of principles, however, looking at the future armed with a set of KPI’s and measurable steps. The nine CSR principles do not elucidate how sustainability is mapped; they do not establish measurable targets for the corporate sector to help furthering the state’s agenda. Yet, India had to start somewhere. Sincerely speaking, we cannot wait for corporations to decide when it is the right time, we cannot just endorse the western voluntariness principle according to which corporations shall grow and thrive by first doing bad and then start cleaning up. State’s carrot and sticks intervention to promote responsible practices is not new. If it wasn’t for regulations, European Union would not have achieved certain remarkable results in terms of reporting and environmental performance.

The other side of the coin, however, is that CSR is not a franchise, it cannot be imposed: it shall mature within a receptive environment where the need to put in place certain practices has naturally evolved. Nevertheless, research shows that sustainability or CSR reporting is often the first action implemented upon kicking off a real integration process. Modern India clearly sees the economic sector as a partner. Thus it not only wants, but requires a change. A drastic CSR-economic revolution finds in regulation the best way to ensure the message is received.

The government needs allies to achieve its ambitious goals, the private sector is now bond to substantiate a social responsibility often blathered but seldom demonstrated. There is no right or wrong in developing such an immense task. There are a plenty of frameworks and national CSR indexed around the world, it is all about choosing the right fit to the current needs. So, this is a bold state-led public-private partnership educational attempt. It all depends on its implementation. A mandated transparency and accountability framework poses the likely risk that companies rush their commitment to comply, creating a superficial strategy as a tick-box exercise.

The act in fact mandates companies to create and disclose a CSR vision, mission and overall philosophy (98 per cent top 100 listed companies complied, 90 per cent provided details), create a CSR committee (64 per cent exceeded the target, 55 per cent include women, 82 per cent have two or more members), expound how the 2 per cent of average net profit has been spent in reference to the policy disclosed. The top 100 companies delivered very well on the strategy and committee creation. However, only 57 per cent presented policy links on their website while just 46 per cent published a detailed road map. Setting a CSR strategy is not an overnight exercise.

It requires awareness, maturity and the inclusion within corporate decisionmaking of societal and environmental concerns, a deep comprehension and prioritisation of stakeholders, awareness of market- and work-place best practices, and especially appropriate governance and processes. Overall, the positivity stands into forcing a “CSR mindset” into companies. The first three to five years will be learning ground; real framework and road maps shall naturally come after this period. The data on the companies’ ability to explicate the CSR spend contribution to the overall plan further confirms the muddle: 42 per cent failed disclosure, 21 per cent did not refer to policy; moreover, only 40 per cent provided details on focus areas and 25 per cent on the stakeholders’ impact. This further demonstrates an early stage of CSR integration, revealing the lack of a fundamental element within corporate sustainability: the materiality principle. Materiality is defined by GRI as the ability of a report or strategy to reflect the organization’s significant socio-environmental impact.

It is an evolving process made of identification, prioritization, assessment and review. This principle asks companies to assess, comprehend, evaluate and include in their decision-making a wide set of responsibilities — governance, society and environment. Companies require time to gauge the situation, pinpoint their strengths, build and test internal processes, and identify partners and focus areas where they can provide the best results to both the society and the company itself. Among the positive notes is the increased average spend, involving 70 per cent companies, with 18 per cent committed to carry on the spend this year. Similarly, the major areas of intervention reflect some of the state’s priorities: health, education, environment and rural development, with philanthropy relegated at 3 per cent.